New article: I wrote about Mitski

On Nov. 9, the indie musician Mitski released her single “The Only Heartbreaker.” It’s clear that she’s returned from her hiatus with a new direction for her upcoming album “Laurel Hell.” (Photo illustration by Natalie Krowitz, photo by Ebru Yildiz courtesy of Pitch Perfect PR)

“Mitski is back. God help us all.”

Earlier this week I wrote a piece for the Washington Square News taking a closer look at Mitski’s two recent singles, “Working for the Knife” and “The Only Heartbreaker,” to see what we can expect from her as she returns from her hiatus.

I’ve listened to a lot of Mitski over the past few years, and I’ve also studied and transcribed a lot of her music — you can find my transcriptions here and a YouTube playlist of my transcriptions here. I wanted to bring a music theory angle to understanding her return because I have a bit of expertise that a lot of the coverage around music lacks.

The piece also features an amazing graphic (above) by my roommate Natalie Krowitz, who’s not only a fantastic illustrator but a caring cat parent. Read the full article on nyunews.com.

Because we aren’t able to upload audio to our website, I’m posting the audio snippets that were meant to accompany the sheet music graphics in the piece.

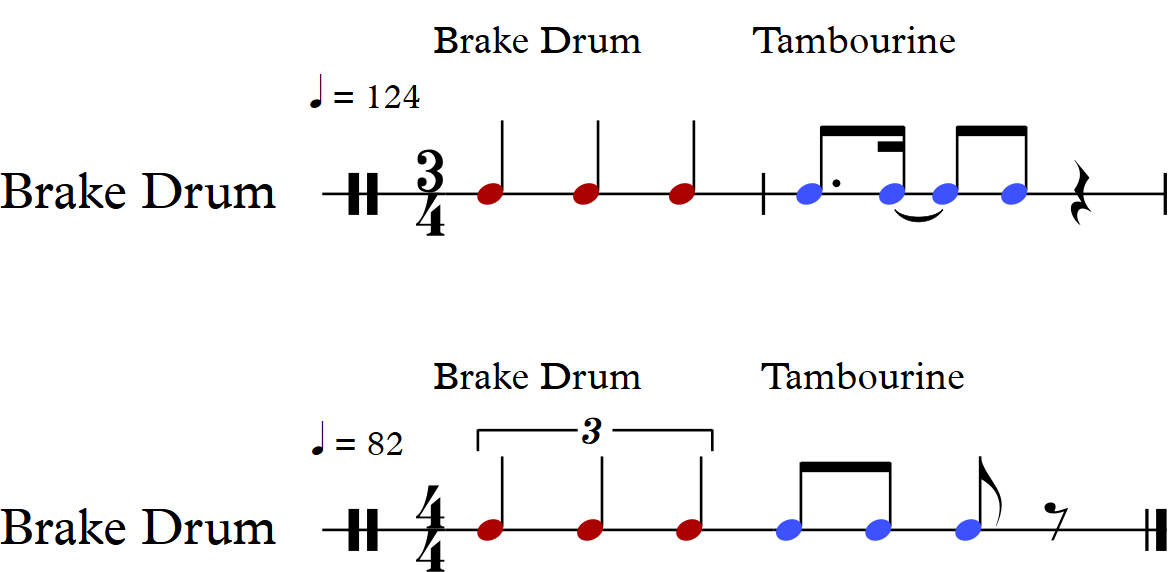

Mitski creates rhythmic ambiguity in “Working for the Knife.” She makes it deliberately unclear which of these two interpretations the listener is hearing.

Here’s what I wrote in the piece about the rhythm from the beginning of “Working for the Knife” that I’ve notated two different interpretations of above:

It’s plausibly deliberate that indecision and ambiguity sit at the very core of the song. The first notes we hear are three metallic, percussive brake drum-like hits, which our ears pick up on as suggesting a meter of 3/4, followed by three slightly faster tambourine hits.

Are the latter group functioning as a group of three in a fast 3/4 defined by the first three quarter notes? Or are the original brake drum hits actually quarter-note triplets in a slower 4/4 set by the tambourine? She deprives us of rhythmic context even when her vocals come in. Without a clear sense of which of two directions we’re being taken in, Mitski suspends her words in another layer of uncertainty.

She’s used this technique of metric ambiguity before — the triplet and 16th-note ambiguity from the beginning of “Goodbye, My Danish Sweetheart” comes to mind — and it’s just as effective here. The listener’s perception of the song’s meter, which we usually judge instinctively, becomes disoriented. We’re not sure which way is up — not sure if we’re floating or sinking. Mitski leaves us to guess at the most basic structures of the music, just as how she’s had to question the role of the music that forms the foundation of her life.

Then, at the 26-second mark, the beat comes in and we fall into a relaxed 4/4 grounded by acoustic guitar and percussion. The other rhythmic elements come into focus, and what was confusing before becomes clear now. Mitski grants us the stability she found for herself.

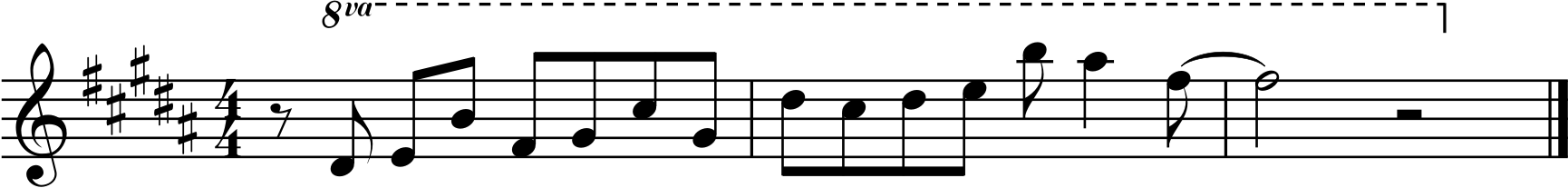

And for “The Only Heartbreaker,” I wrote about this particular synth lick (or maybe guitar? I’m leaning synth, though) about halfway through the song.

The synth line at 1:27 of “The Only Heartbreaker.”

In typical Mitski fashion, this track juxtaposes gut-wrenching lyrics with upbeat instrumentals like a cheerful synth and peppy drum machine.

Interspersed with her refrains is a synth line that grounds the song with measured precision. It is painstaking and deliberate — the opposite of the raw emotion on her 2014 breakout album “Bury Me at Makeout Creek” and 2016 follow-up “Puberty 2.” The lick leading up to the main impact of the song about halfway through the track is particularly intricate, ascending with melodic exactitude like a mechanical skylark.

Though I focused on this one musical quote in particular, I found that synth part to be a key feature of the track. Not only does the chosen patch establish a confusingly upbeat 80s mood, its constant melodic changes (there’s no single motif repeated throughout the song) maintain an unrelenting rhythmic precision.

It drove the song forward, even uncomfortably so. To me, this evoked how Mitski is forcing herself to move on from the subject of the song, even though she may not be ready to.